Fair Use in More Detail

Updated: 5/8/2019

Original publication: 5/11/2017

The purpose of copyright law was never to close down the exchange of ideas; in fact, it exists to encourage creators to share their work without fear of others stealing or profiting from it. In the spirit of exchanging and building on others’ ideas, fair use permits people to use limited portions of copyrighted works without obtaining permission from the copyright holders, for the purpose of criticism or commentary. This article dives into the specifics of how to evaluate whether your use of a copyrighted work in the online class qualifies for fair use.

Fair Use Guidelines

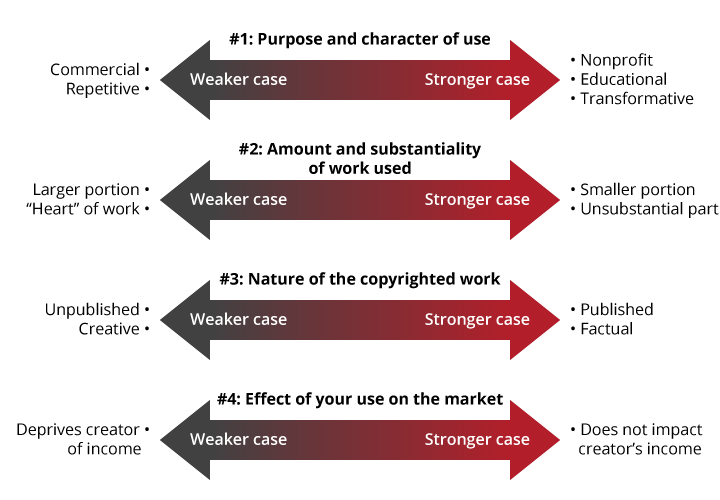

There are four standards that you must consider when deciding whether fair use protects your use of a copyrighted work. You can use the acronym PANE to help you remember them:

- Purpose and character of the use

- Amount and substantiality of the portion used

- Nature of the copyrighted work

- Effect of the use upon the potential market

Keep in mind that fair use is a subjective legal issue; that is, opinions may vary on whether your use of a copyrighted work is “fair.” Think of each of these guidelines on its own sliding scale, as in the image below (adapted from University of Minnesota Libraries, 2011):

If you make your best effort to adhere to the following four standards and have strong arguments for each one, you can be confident that you are benefiting your students while still respecting copyright law.

The next sections take a close look at how to evaluate each of the four factors.

The Purpose and Character of the Use

The purpose of the use refers to whether you are using the work for nonprofit or educational purposes or for commercial (for-profit) purposes. Generally, copyright law favors nonprofit or educational uses over commercial uses. Note: If you work for a for-profit university or educational service, your use of a copyrighted work will likely be considered commercial even if it’s for educational purposes.

The character of the use refers to whether your use of the work is transformative rather than merely replicative. In other words, your use should somehow add to the original work or contribute new insight into the topic rather than merely repeat the original creator’s ideas.

| Acceptable | Not Acceptable |

|---|---|

|

|

The Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used

The amount refers to the quantity of the work used. Although many have suggested that 10 percent is the acceptable amount of a work you can use, the law doesn’t actually specify a certain percentage. However, in general, the smaller the percentage, the more likely it is that your use will be considered fair.

A note on images: Images are difficult because typically it is necessary to display the entire image rather than just a portion of it. If you need to use a full image, make sure your use complies with the requirements of the TEACH Act. (See our article The TEACH Act in More Detail for more information.)

Substantiality refers to the quality of the portion of the work you use. In other words, it matters what part of the work you intend to include in your course, not just how much. Copyright law provides stronger protections for the “heart” of a work, meaning what makes the work unique or iconic. For example, fair use would likely not cover replicating the argumentation or structure of an essay or “borrowing” the most memorable lines from a movie, even if they constitute a small portion of the work.

| Acceptable | Not Acceptable |

|---|---|

|

|

The Nature of the Copyrighted Work

The nature of the work refers to two main issues: (a) whether the work is published or unpublished and (b) whether the work is more creative or factual. Copyright law favors authors’ right to choose when and how they first publish their works, so fair use is less likely to allow the use of an unpublished work. Copyright law also more stringently protects creative works because they are more unique to the creator than factual works.

| Acceptable | Not Acceptable |

|---|---|

|

|

The Effect of the Use Upon the Potential Market

Your use of a copyrighted work may not deprive the original creator of any income he or she may currently earn or earn in the future based on the work. For example, instructors might deprive a filmmaker of income if they screen a DVD meant for individual purchase, or they might deprive publishers of income if they summarize large portions of a textbook that students might otherwise buy themselves.

You also may not create derivatives of someone else’s work. For example, you can’t take a series of essays and turn it into a book or create a piece of art based on a photograph, because this would deprive the original creator of the chance to earn income based on his or her work in a different industry.

| Acceptable | Not Acceptable |

|---|---|

|

|

Conclusion

When considering whether your use of a copyrighted work falls under fair use, ask yourself these four questions:

- Are you using the work for educational purposes, and does your use expand on the original work in some way?

- Is the original work published and factual in nature?

- Is your use a reasonably small portion of the entire work, and does it avoid using the “heart” of the original work?

- Does your use avoid depriving the original creator of present or future income?

If you can answer “yes” to most or all of these questions, you can be confident that your use of the work is legal and ethical. Just make sure to cite your source!

For more information on how you might be able to use copyrighted works in your online classroom, check out our article Copyright and Plagiarism: The Bare Minimum Instructors Need to Know.

References

American University Library. (2010). What faculty need to know about copyright for teaching. Retrieved from https://www.american.edu/library/documents/upload/Copyright_for_Teaching.pdf

Columbia University Libraries. (n.d.). Fair use. Retrieved from https://copyright.columbia.edu/basics/fair-use.html

Hoon, P. (2007). Using copyrighted works in your teaching FAQ: Questions faculty and teaching assistants need to ask themselves frequently. Retrieved from http://www.knowyourcopyrights.org/storage/documents/kycrfaq.pdf

Stanford University Libraries. (n.d.). Measuring fair use: The four factors. Retrieved from http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/fair-use/four-factors/

University of Minnesota Libraries. (2011). Can I use that? Fair use in everyday life. Retrieved from https://netfiles.umn.edu/users/nasims/Share/FairUseforFacultyRev10_2011.pdf